Los protones, neutrones y electrones parecen ser bastante extravagantes en el universo, aunque a nosotros nos parezca que lo extraño sería cualquier otra cosa que no tenga esas partículas

Recopilamos algunas de las muchas preguntas que fuimos presentando en los últimos artículos: ¿Hay cosas que no vemos y que escapan a nuestros telescopios? ¿Hay materia que ni emite ni refleja la luz, que pasa de ella completamente? ¿Y si mirar no es la única ni siquiera la mejor forma de conocer el universo?

En realidad, la respuesta a todas esas preguntas ya la dimos en el primer artículo dedicado a la luz: la materia oscura existe sí o sí. Dijimos que otra cosa es el exotismo de la materia oscura. Y para los astrofísicos el concepto de materia oscura es exótico. Lo explicamos a continuación con bastantes más preguntas.

Los filósofos presocráticos consideraban que la materia estaba constituida por cuatro elementos básicos y, hoy en día, pensamos que la existencia de todo lo que vemos a nuestro alrededor se basa en cuatro tipos de interacciones entre partículas llamadas campo fuerte, débil, gravitatorio y electromagnético.

Los protones y neutrones forman los núcleos de átomos, y ellos mismos están formados por quarks que permanecen juntos porque existe una interacción llamada fuerte, que es extremadamente potente, de ahí su nombre (los físicos no se quiebran la cabeza con los nombres). Es tan potente que los protones pueden mantenerse juntos en los núcleos de los átomos incluso aunque tengan cargas eléctricas positivas. Pero el campo electromagnético, que es repulsivo para cargas iguales, es menos intenso que la interacción fuerte a escalas subatómicas.

Otro campo es el llamado débil, que tiene una intensidad cien veces menor que la interacción fuerte (de ahí su nombre, más simpleza lingüística para algo que no es nada sencillo). La interacción débil es extremadamente importante, por ejemplo es la responsable de que uno los 3 quarks que componen los neutrones cambie de propiedades (el llamado “sabor”, más historia con los nombres que dan los físicos) y estos últimos no sean estables, sino que tiendan a convertirse en protones (salvo que estén en un núcleo atómico). Este fenómeno parece poco relevante para cualquier persona, pero explica que la mayor parte de los átomos del universo sean de hidrógeno, y este se haya podido juntar con oxígeno para dar algo tan importante para la vida como es el agua. Sin la fuerza débil, en los primeros minutos del universo los neutrones habrían resistido enteritos y se habrían combinado con protones para formar núcleos como los de helio, al que le gusta combinarse poco, así que la química habría sido bastante aburrida y no existiría el mundo que conocemos.

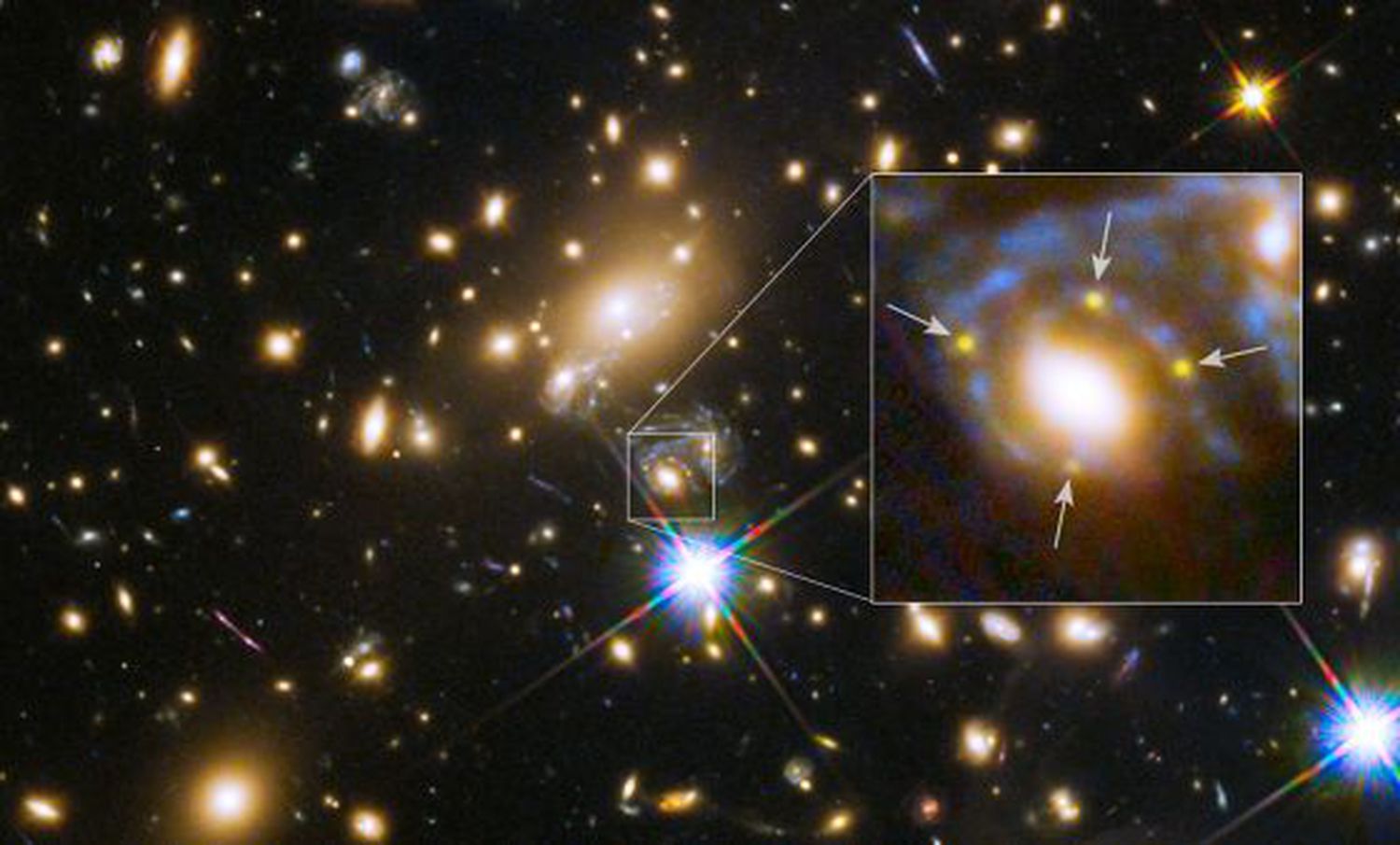

La última interacción fundamental es la gravitatoria, que en principio actúa sobre cosas que tienen masa y es siempre atractiva. Los fotones, que son la representación en partícula del campo electromagnético, se dice que son sus mensajeros, no tienen masa. ¿Les afecta el campo gravitatorio? Si nos ceñimos a la Ley de Gravitación Universal de Newton, que establece que la fuerza gravitatoria entre 2 objetos depende de la multiplicación de sus masas, la respuesta sería no. Pero hoy está demostrado, gracias a la Relatividad General de Einstein, que a los fotones sí les afecta la gravedad, incluso aunque no tengan masa. El efecto es extremadamente pequeño, pero existe y da lugar a algunas de las imágenes más bonitas del universo, como son las cruces de Einstein, y a que existan los agujeros negros.

Los neutrinos que crea el Sol típicamente pueden atravesar todo el material de nuestra estrella sin inmutarse, mientras que los fotones tardan cientos de miles de años

A los fotones, entonces, que son los portadores del campo electromagnético, prácticamente no les afecta otra fuerza fundamental como es la gravitatoria. ¿Hay partículas a las que no afecta el campo electromagnético y solo interaccionan con otras partículas a través de algún otro campo fundamental? Serían partículas que no son nada sociables con los fotones, de ningún tipo, visibles, rayos-X, infrarrojos,..., que no interaccionan con ellos. La respuesta es sí, las hay: los neutrinos, que además no se relacionan tampoco con campo fuerte ni tienen gran masa para interaccionar mucho gravitatoriamente. Solo sabemos de ellas por la fuerza débil, que es muy poco intensa, así que por ejemplo los neutrinos que crea el Sol típicamente pueden atravesar todo el material de nuestra estrella sin inmutarse, mientras que los fotones tardan cientos de miles de años. Los neutrinos, además, pasan a través de nosotros y de toda la Tierra sin que nada los pare o los desvíe (prácticamente).

¿Hay partículas como los neutrinos, pero que tienen masas más grandes que ellos y que no interaccionan prácticamente con nada de lo que conocemos, sobre todo con los campos electromagnéticos? Pues la respuesta para los astrofísicos, y para muchos físicos de partículas, es sí, tienen que existir, pero no las hemos descubierto aún de forma directa. Estas partículas interaccionan con otras con fuerza débil como los neutrinos, pero tienen una masa bastante mayor. En inglés serían weakly interacting massive particles, WIMP, partículas masivas que interaccionan débilmente.

Llamar WIMP a esas partículas es como hablar de fruta, es un nombre muy genérico, y no nos dice gran cosa de sus particularidades. Podrían ser “sandías” o “cerezas”. Según nuestros estudios sobre las galaxias, cúmulos de galaxias y el comportamiento global del universo, tenemos bastantes pruebas de su existencia, deben ser la materia más abundante que existe, un 85% de todo lo que tiene masa, dejando solo un 15% para nuestros protones, neutrones, electrones, neutrinos,... Al ser materia que no interacciona con fotones, ni los absorbe y se calienta ni los emite y se enfría, es materia que no podemos o es muy difícil detectar con radiación electromagnética, no la vemos, es “materia oscura” pata negra, nuestra definición precisa para los astrofísicos. Podría calificarse como materia “procedente de un lugar lejano y percibida como muy distinto del propio”, sería materia oscura exótica de acuerdo a la RAE.

Nuestro único problema, bastante gordo es verdad, es que no hemos conseguido aislar ningún WIMP en un laboratorio, y lo hemos intentado. Y por eso este tipo de materia nos resulta “extraña, chocante, extravagante”, otra de las acepciones de exótica. O nos hemos equivocado mucho o aún no hemos sido capaces de detectarla, lo cual no es impensable porque estamos buscando algo que no interacciona casi con la materia normal ni con los fotones y lo estamos haciendo precisamente con instrumentos basados en materia normal y fotones. Es como querer coger agua con una raqueta de tenis. Cualquiera que sea la respuesta, tanto si los WIMPs existen como si no, significará un gran descubrimiento científico cuando la encontremos, sabremos mejor de qué material está hecho la mayor parte del universo.

Pablo G. Pérez González es investigador del Centro de Astrobiología, dependiente del Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas y del Instituto Nacional de Técnica Aeroespacial (CAB/CSIC-INTA)

Patricia Sánchez Blázquez es profesora titular en la Universidad Complutense de Madrid (UCM)

Vacío Cósmico es una sección en la que se presenta nuestro conocimiento sobre el universo de una forma cualitativa y cuantitativa. Se pretende explicar la importancia de entender el cosmos no solo desde el punto de vista científico sino también filosófico, social y económico. El nombre “vacío cósmico” hace referencia al hecho de que el universo es y está, en su mayor parte, vacío, con menos de 1 átomo por metro cúbico, a pesar de que en nuestro entorno, paradójicamente, hay quintillones de átomos por metro cúbico, lo que invita a una reflexión sobre nuestra existencia y la presencia de vida en el universo.

Fuente: https://elpais.com/ciencia/2020-12-02/el-universo-exotico.html

:quality(85)//s3.amazonaws.com/arc-wordpress-client-uploads/infobae-wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/23034024/FB_IMG_1569215013430.jpg)

:quality(85)//s3.amazonaws.com/arc-wordpress-client-uploads/infobae-wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/11125804/agujeros-negros-mexico-foto-naranja-nyt.jpg)

:quality(85)//s3.amazonaws.com/arc-wordpress-client-uploads/infobae-wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/23110225/star-trails-828656_1920.jpg)

:quality(85)//s3.amazonaws.com/arc-wordpress-client-uploads/infobae-wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/19112901/chile-agujeros-negros-1920.jpg)

:quality(85)//s3.amazonaws.com/arc-wordpress-client-uploads/infobae-wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/10081435/Agujeros-negros.jpg)

:quality(85)//s3.amazonaws.com/arc-wordpress-client-uploads/infobae-wp/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/11124044/agujeros-negros-mexico-nyt.jpg)